Alec Tzannes is the Founding Director of Tzannes, a leading architecture and urban design practice based in Sydney. He established the studio’s distinctive design philosophy, with its emphasis on intellectual rigour, collaboration, sustainability and a strong sense of ethics. He has served as the Dean of Built Environment at UNSW and in 2018, was awarded the Australian Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal, its highest individual honor.

Tzannes is a leader in designing Australia’s built environment – from homes, workplaces, and institutions to large city-shaping projects. The practice’s work spans beyond the architecture of a building, seamlessly integrating across design disciplines.

Over the past 40 years, Tzannes’ commitment to design excellence has been recognised with over 200 international, national and state awards. Tzannes also been honoured for their work in commercial buildings, sustainable timber structures and for innovation in street furniture design.

Global Design News spoke to Alec Tzannes about his work, and how Tzannes approaches architecture and design from the perspective of the thriving international city of Sydney.

What do you consider the defining elements of your architectural legacy, and how does Tzannes embody those values today?

Tzannes has established a strong reputation for design excellence over four decades across a wide range of typologies, beginning in architecture and subsequently expanding to include urban design, interior architecture, industrial design, and product design.

While the projects that have achieved significant recognition are important, even more important is the shared foundation values of our studio led today by Amy Dowse (Director, Tzannes). We maintain and continually evolve our distinctive approach to design.

We maintain an active engagement with the fast moving advances of knowledge relevant to our work and evolve our distinctive approach to design without losing sight of our values and historic strengths.

We always start from ‘first principles’, which is a way of summarising how each design is founded on evidence-based research to understand place, typologies and the expressive potential of space, form, light and functionality.

We integrate new knowledge into the design process to advance beyond the status quo. We focus on outcomes that serve our client’s brief and are embedded in a commiment to the wider public interest.

We don’t commodify our work as products directly tied to our identity. Our work is always original, place specific, designed to endure, and appreciate in value.

We are acutely aware of the need to establish a new form of beauty relevant to design that contributes to lowering carbon emissions, is adaptable including capacity to be disassembled and recycled, and always socially connected to time and place.

How has your heritage and study of Greek architecture shaped your design sensibilities and approach to urban design?

My natural bias is towards design that has innate order – a feeling of being a natural fit with place and purpose. The sense of proportion, use of materials, integration of structure, the way light shapes form and the experience from movement through and around places as well as the functions within buildings, contribute to the innate order and composition of design propositions.

I am probably in the classical tradition of urban design and architecture, concerned with its evolution to address contemporary concerns.

My studies include the pre-industrial vernacular urbanism of Greek villages and the sophisticated designs by Pikionis around the Acropolis, as well as the architecture of Delphi and the Parthenon – just some examples of how Greek design culture has shaped my design sensibility.

How do you balance aesthetics, functionality, building codes, sustainability and decarbonisation in your design process, especially in larger, complex projects?

Design for me is about the comprehensive integration of a unique proposition shaped by understanding place and time, combined with the imperative to optimize functionality expressed through the principles of tectonics, such as the utilization of the expressive potential of structure, environmental performance, material selections and special details.

I aim to deliver design that improves with age, continue to engage over time with interest and emotional impact, is useful, and address the relevant concerns of our era.

Could you discuss your role in leading a multidisciplinary team on the Brewery Yard project and how you ensured the high standard of detail and craftsmanship envisioned by the client?

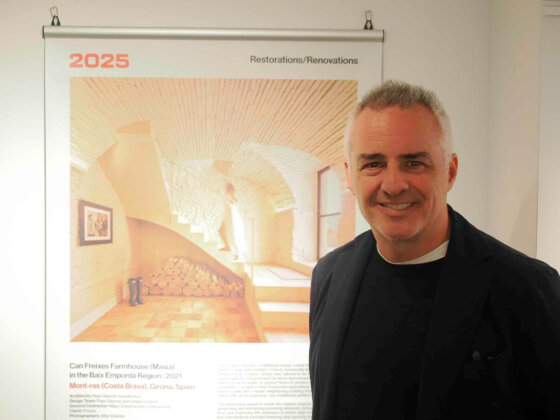

The adaptive reuse of the historic Kent Brewery in Sydney’s Central Park transformed several significant early 20th-century heritage buildings into a single complex at the heart of the precinct, the former site of the historic 6.7-hectare Carlton and United Brewery Yard.

Our role started over two decades ago when we were appointed to undertake the master plan for the Central Park precinct following an Australia-wide national competition. Once the master plan was legislated, we were appointed to undertake the adaptive re-use of the Brewery Yard historic buildings for two different clients in two stages.

Stage 1 for client Frasers involved establishing, under the Brewery Yard courtyard and above the historic fabric, a rooftop tri-generation energy plant to serve the Central Park precinct and part of the adjacent University of Technology campus.

Stage 2 for client IP Generation involved the adaptive re-use of the historic brewery building, sensitively adding more floors to improve functionality. We created a distinctive workplace that integrates the interpretation of the historic fabric and industrial artefacts from previous uses as part of the overall experience of the place and its interiors.

We led the multi-disciplinary design team working with our client to make design judgements that maintained the unique qualities of the original building, guided by the Conservation Management Plan prepared by Urbis, inserting new elements that enhanced the experience within the building and precinct.

We worked closely with cost estimators whilst leading the team to ensure our design propositions were implementable at the highest available level. We detailed the construction documents and attended the site in our capacity as architects, always being open to solving challenges as they arose. We effectively advocated design solutions that enhanced the experiential qualities of the interiors and the greater role the architecture plays in the public domain.

When unforeseen issues became evident on site, a common phenomenon in adaptive reuse projects, we worked with the team, always advocating for design-led solutions that did not compromise the integrity of the design intent.

As a former Dean of the School of Built Environment at the University of New South Wales (in Sydney) and as a mentor, how do you see architectural education evolving to prepare future architects for industry challenges, and which trends will most shape architecture and urban design in the next decade?

As the environment of our planet continues to be deeply challenged by the growth of human population and the need to expand built infrastructure, I summarize some of the main objectives of architecture and urban design education as follows.

- Deliver graduates capable of maintaining the confidence of the wider society through their sound discipline and professional knowledge, values, critical thinking capabilities and ethical practices. This secures the role of design in public policy, management of places and the integration of design-led construction to implement enduring and sustainable urban change.

- Ensure our graduates fully engage with and understand developing knowledge in environmental sciences, including urban and building physics to ensure their design decision framework is grounded in environmentally sustainable objectives.

- Equip our graduates with an understanding of new technologies in design, including the rapidly evolving application of AI, prefabrication, which encompasses disassembly and material sciences.

- Expand design thinking by engagement with the advancement of aesthetic ideas that are often most accessibly expressed for designers through other visual arts.

- Study density at every level of design education, as this is a primary way we can contribute to the reduction of urban sprawl and protection of the habitats of other sentient beings, among other benefits.

- Enable a 12-month exploration of design for the graduating class underpinned by a specialisation theme.

For example, at UNSW Architecture, final-year students following a solid grounding in professional design practice complete their design program by choosing to focus on one of four different studio themes: High Performance Architecture (HPA), Housing, Urban Conditions, and Social Agency.

HPA involves complex high technology design briefs. Housing explores specific typologies developing specialist knowledge. Social Agency is innovative from an educational perspective as it aims to explore ways of thinking and designing for communities living in places of dire urban poverty, often with completely different cultural practices including building typologies.

The different themes overlap – what is common is the emphasis on empowering the designer to think freely and in the process create a new form of beauty that has relevance to a better future for all.

About Tzannes

Tzannes is a leader in designing Australia’s built environment – from homes, workplaces, and institutions to large city-shaping projects. The practice’s work spans beyond the architecture of a building, seamlessly integrating disciplines as distinct as urban design, interiors and industrial design.